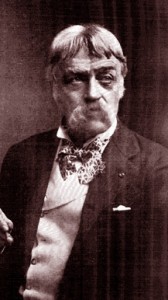

A century after his death, Frank Furness is the most fashionable man in Philadelphia.

The Victorian-era architect’s Gothic-inspired designs include the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, which includes structural elements that enabled Furness protege Louis Sullivan to design the first skyscrapers.

The Victorian-era architect’s Gothic-inspired designs include the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, which includes structural elements that enabled Furness protege Louis Sullivan to design the first skyscrapers.

PAFA’s retrospective, Building a Masterpiece: Frank Furness’ Factory for Art, is scheduled to run Sept. 29-Dec. 30. But it’s already in place, so if you want to avoid the crowds, go now. (We also will be looking at other fabulous Philly destinations over the next week.)

Serendipitously, The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins’ masterpiece depicting an anatomy class, also is in residence through January at PAFA, where Eakins studied in the mid-19th century and where artists still train today. So there are twice as many reasons to indulge in this uniquely Philadelphia artistic experience. (The freight elevator, used to bring in cattle and other large animals, still transports an occasional horse for students to sketch.)

Serendipitously, The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins’ masterpiece depicting an anatomy class, also is in residence through January at PAFA, where Eakins studied in the mid-19th century and where artists still train today. So there are twice as many reasons to indulge in this uniquely Philadelphia artistic experience. (The freight elevator, used to bring in cattle and other large animals, still transports an occasional horse for students to sketch.)

Furness was born in Philadelphia in 1839 and died nearby in Nether Providence Township, Pa. in 1912.

In between, he served in the Civil War, earning the Congressional Medal of Honor for volunteering to carry ammunition to stranded soldiers across the open battlefield. (Learn about his military career at an exhibit the Historical Society of Frankford.) He served at Gettysburg, later designing a memorial there, and is buried at the hauntingly beautiful Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, also the final resting place of George Gordon Meade, who led Union Forces to victory at Gettysburg.

In between, he served in the Civil War, earning the Congressional Medal of Honor for volunteering to carry ammunition to stranded soldiers across the open battlefield. (Learn about his military career at an exhibit the Historical Society of Frankford.) He served at Gettysburg, later designing a memorial there, and is buried at the hauntingly beautiful Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, also the final resting place of George Gordon Meade, who led Union Forces to victory at Gettysburg.

Furness and business partner George Watson Hewitt won a design competition to design PAFA, to be completed in time for the Centennial of 1876.

The Long Recession, which dragged on from 1873-1879, resulted in budget cuts. The concrete floor on the second level looks amazingly hip for Victorian times but in truth it’s much cheaper than marble. Blank friezes on the exterior, a counterpoint to the ornate facade, also were an economy measure.

There’s still lots of bling, with extravagant carved rosettes, gilding and sweeping staircases. It’s an amazing and clever building, with such innovations as skylights and the “curtain walls” that made skyscrapers possible. Exposed I-beams are part of the design. Cast iron pipes are trimmed out and decorated as columns. The spindles on the sweeping staircase are artistic interpretations of gears and piston rods cast in brass.

Furness — pronounced FUR-ness — is hot as, well, a furnace these days. But his heavy, ornate Gothic designs fell out of fashion in the mid-20th century as architects embraced minimalism. Many of Furness’ buildings were knocked down. His elaborate interiors at PAFA were sheetrocked over in the 1950s, hidden behind plain vanilla walls until a restoration in 1976.

His largest collection of railroad buildings, a trio of red brick structures including what is now the Amtrak station, are sited on the riverfront in Wilmington, Del. You will find Furness’ touch throughout Philadelphia and the ‘burbs, from the First Unitarian Church on Chestnut Street, where Furness’ father was pastor, to Merion Cricket Club.

Clearly, Furness built them to last.